Storybox 01:

This is quite certain;

no one of us can deny it:

are you contented that

it should be so?

[01] Izi Thexton

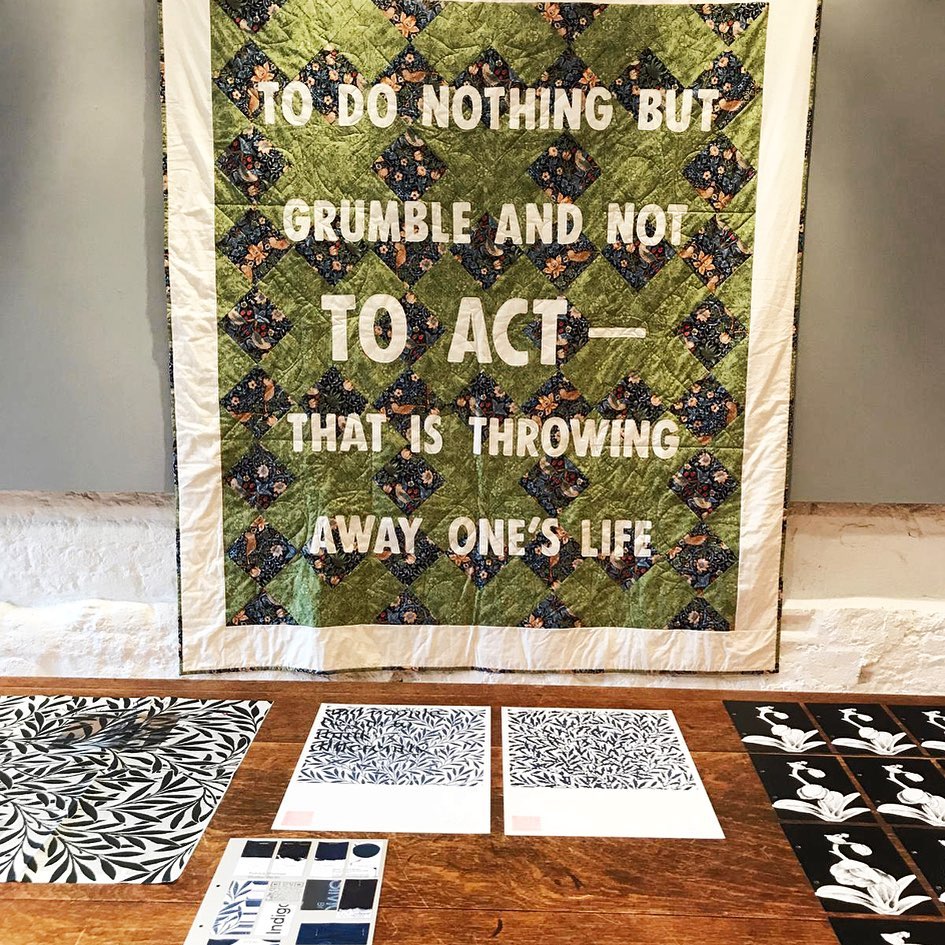

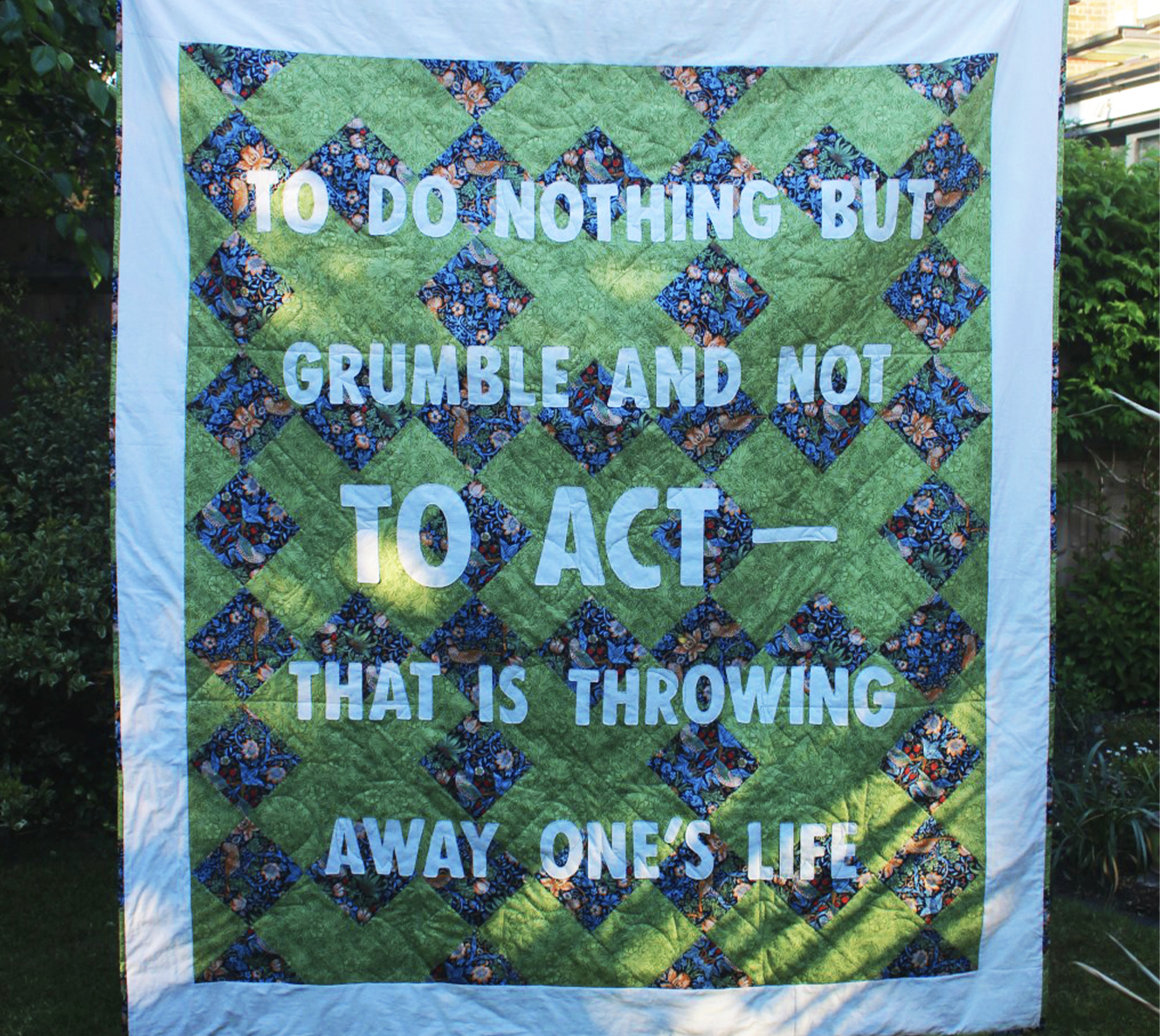

To Do Nothing.

A quilt depicting a quote from Morris from over 150 years ago, demonstrating how he predicted the unsustainable nature of capitalism and the climate emergency we find ourselves in today. ‘Blanketing’ is a traditional ceremony held by certain indigenous communities, whereby a quilt is placed over an individual as a sign of respect and forgiveness. The term ‘to blanket’ also means to cover up, to stifle, and to affect everyone (as in ‘blanket term’). This bears relevance to our complacency in this climate crisis, and our reluctance to change despite the facts. The pattern on the quilt forms ‘X’ shapes and hourglasses in William Morris fabric, referencing protest, Extinction Rebellion, how so much time has passed and that the clock is ticking. In this way, the quilt links the past, present, and future, as the quilt hangs open in the exhibition space; waiting for change to come and someone to forgive.

website: izithexton.co.uk

instagram: @izi.thexton

[02] Chloe Hulse

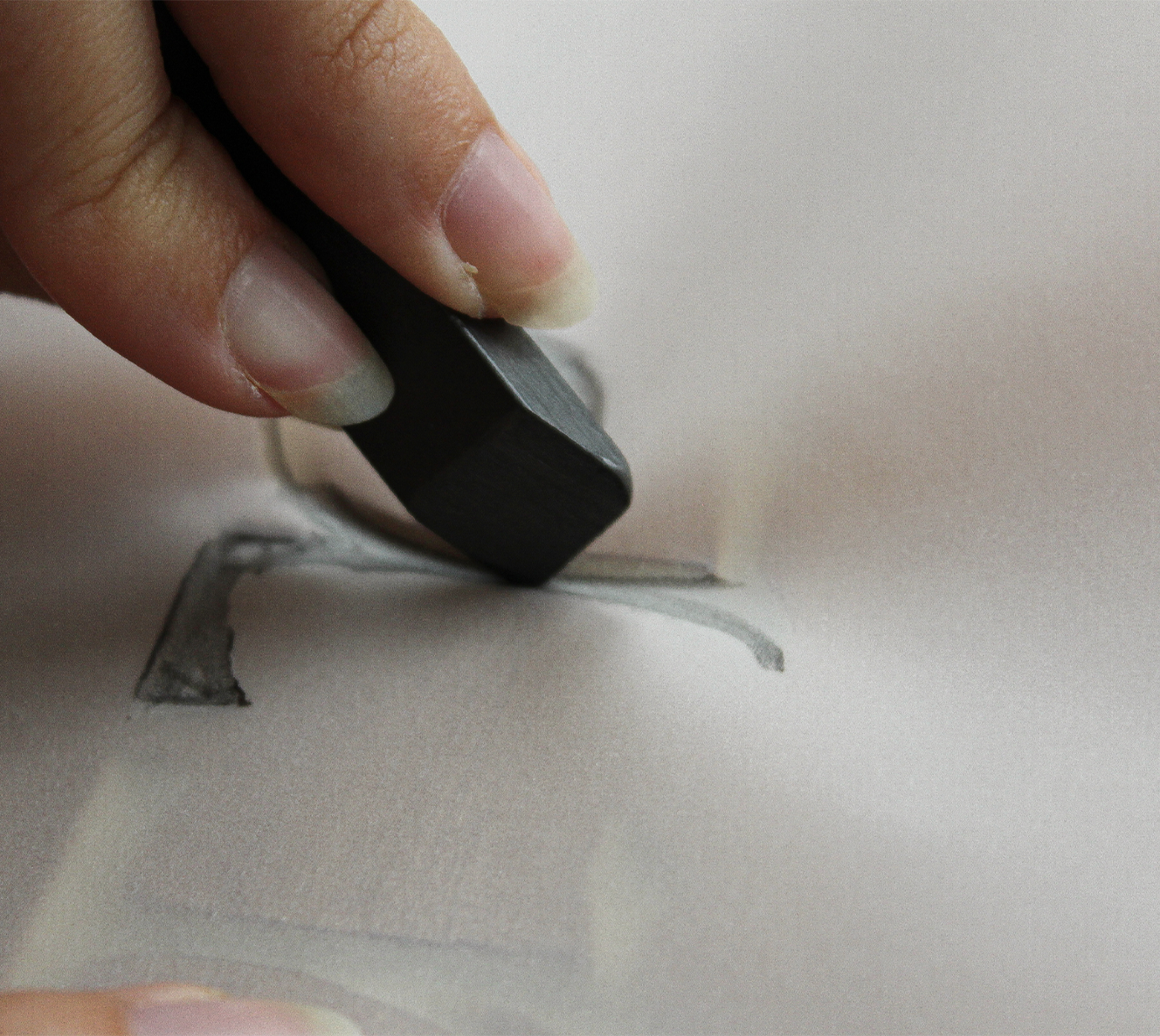

William Morris championed the importance of craft; his eco-socialist ideology hinges on the idea that beautiful, well-made objects reduce waste and bring fulfilment to the lives of craftsmen. Inspired by Morris, I aimed to learn an endangered craft: letter cutting—the art of cutting letterforms using a chisel. Taking years to master, the difficulty of the craft is putting off many prospective letter cutters and, with less than one hundred professionals still working in the UK, it has recently been added to the Heritage Craft Association’s list of endangered crafts. Working to change this, I designed a bespoke set of letterforms specifically for the use of a chisel, making them easier to cut, and used them to create six letter-cut wooden tablets. Using one of these hand-cut tablets, I then made a series of embossings into paper and letterpress-printed a summary of Morris’s ideology onto them—creating my own version of Morris’s popular ‘penny pamphlets’*. The project culminated into a letter cutting workshop where I invited young creatives to learn about the craft. In exchange for a ‘penny pamphlet’, participants made tracings of my letter cuttings with chisel-shaped graphite sticks, producing a collection of graphite posters expressing what art and crafts mean to them.

* ‘Penny pamphlet’ was the term coined for Morris’s smaller, cheaper reproductions of his books. While the originals were limited and expensive, his ‘penny pamphlets’ were accessible to many more people, educating a wider audience onthe general ideas he explored in his longer texts.

Instagram: @chulse.design

[03] Julia Rose Lewis

My contribution is a series of blackout or found poems from his writing about the ornamental arts. The poems make use of his words in the exact order in which he wrote them, although the selection of which words to discard and how to reimagine the punctuation was my own. In 1881, William Morris gave a lecture at the Working Men’s College entitled, ‘Some Hints on Pattern-Designing.’ His lecture sets forth his principles of design and makes a clear distinction between the fine arts and ornamental arts. It is important to note, that he does not consider one more significant than the other. Prior to reading this lecture, I had given little thought to pattern-designing with respect to the ornamental arts. However, I had dedicated some time to studying the role of patterning in developmental biology, I found that one echoed the other quite clearly in my mind. From fruit flies to humans, pattern formation is essential as the organism unfolds through space and time. Artists (ornamental and otherwise) and developmental biologists alike are concerned with patterns and how creating new or different patterns can affect the quality of our lives.

[04] Annie Yonkers

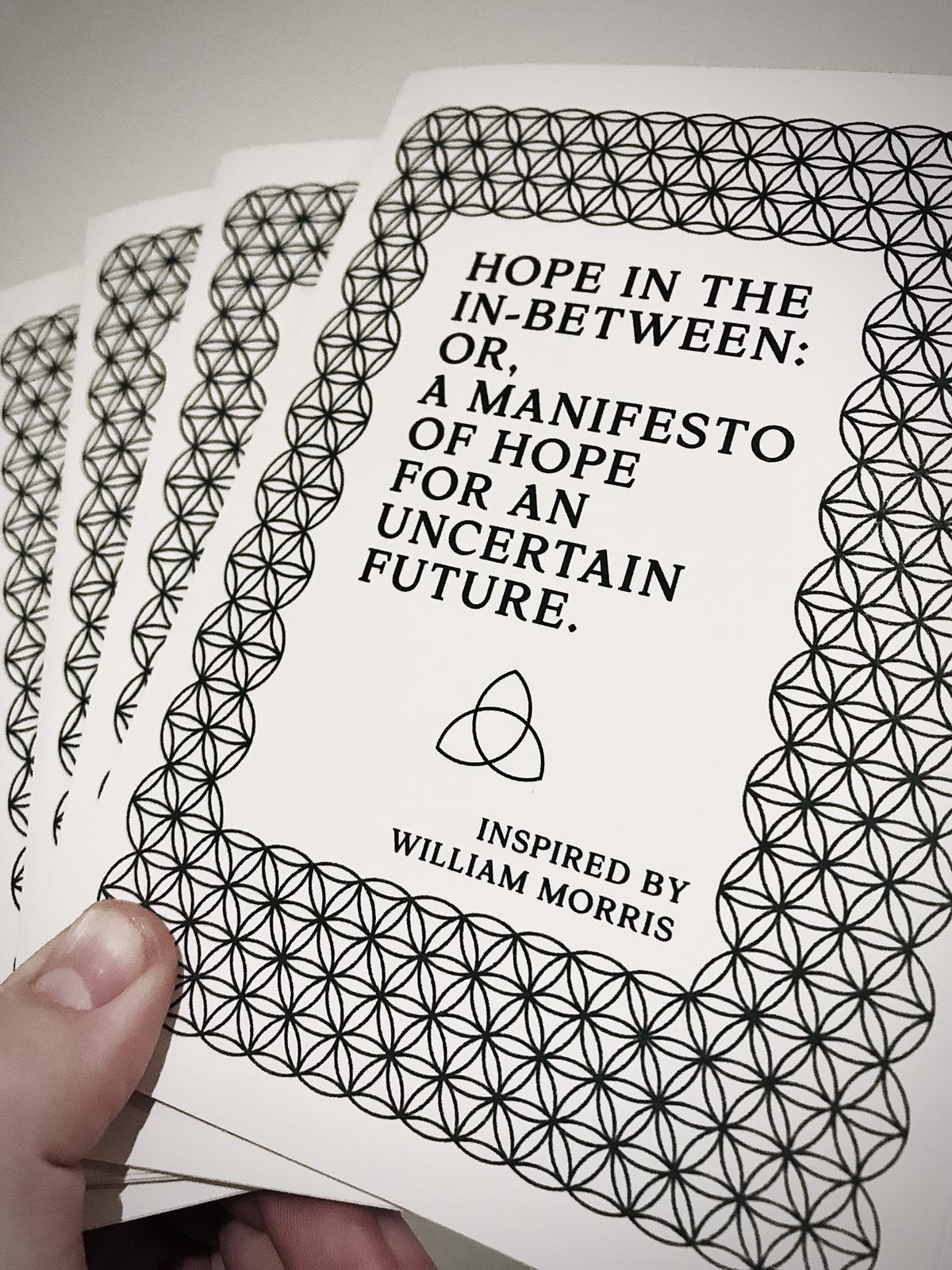

Certain themes presented in News from Nowhere took on a new meaning in Lockdown. The lines between work, leisure, education became increasingly blurred as we were forced to do all three in a space that was (for most of us) a place of respite for either work or education. The spaces we occupy, how we use them, and what we do within them is changing before our eyes, and I wanted to explore these “in between” spaces -between work and education, between education and living, between living and work. Now is our opportunity to realize Morris' vision and actively challenge why, how, and where we work, live, and learn.

My project, heavily inspired by Morris’ written work during his later years and time in the Socialist League, draws parallels between themes and quotes prevalent in his challenges of these areas of life, and my own experience of questioning the same themes during lockdown and beyond. Printed on the Albion Press at Kelmscott House, it’s a tangible callback to the pamphlets printed there over 100 years ago, with themes that are just as relevant as ever.

Instagram: @annie.yonkers

website: makeshittogether.com

[05] Ioanna Stergiaki

The importance of traditional craftsmanship and how the role of an upholsterer in 2020 has been affected by the modern furniture industry reflects and draws on aspects of information that I acquired whilst I was a traditional upholstery apprentice from 2017 – 2019.

Craftsmanship in both its past and current states remains a practice of high skill and is largely unchanged within its own sphere. The disturbance has been caused by factories and their brisk presence feeding our consumerist habits. This deep-rooted issue is demonstrated across all aspects of society in some form. We speak regularly in the past tense about the loss of tradition, quality and sustainability in a variety of conversations in connection to eco-socialism today. Is it nostalgia for a world we never knew or a drive to challenge capitalism?

Touching on socialism and the ‘workshop mentality’ combined with late 19th century utopian ideals, this piece of writing aims to provide an insight into what makes a person a craftsman and more specifically asks, is there a place for traditional upholsterers in a society where the modern furniture industry seems to be unapologetically thriving? The fundamental aspects of how we approach things must be questioned; from both an educational angle on how we value apprenticeships to the magnitude of the damage to the natural world.

Let it urge us to debate and revaluate our role.

Instagram: @i.stergiaki

[06] Dionne Kitching

William Morris’s News From Nowhere is considered to be the first eco-topia, the first Utopian novel to imaging our future intertwined with nature, where there is no extractive capitalist system, no government, but a truly equal society, where art and nature take centre stage.

My drawings for this project are about imagining Utopia, the importance of imagining a radically different future and how this can influence our actions in the present. In a changing world, perhaps Utopian thinking can help us shape the future.

Rooted in studies of Morris’s botanical designs I used local flora as a starting point for my drawings, and brought in themes relating to Utopia, the impossibility of Utopia, beauty, humanity, femininity and nature. Finally these were printed using a Risograph printer, using soy based inks.

Instagram: @dionnekitching

twitter: @dionnekitching

website: dionnekitching.co.uk

[07] Cecily Loveys Jervoise

I am a scavenger, digger and collector. An artist, environmentalist and imperfectionist. I thrive foraging in bins and bushes for the perfect piece of plastic or dainty dead flower. Revolving around material cycles and stories, I seek to incite civic responsibility through visualising a new, all hailed eco-materialistic space. These foraged clay ceramics are emblematic of my exclusive use of foraged natural or copious waste materials. This ecological outlook aims to repair a disconnect with nature and acts as a personal cathartic practice to process the undoing of the planet in the climate emergency. These ceramics are slowly and lovingly fabricated from clay I dig up where I grew up in Devon. They are smoke fired with various foraged natural materials such as manure, seaweed, leaves and seeds; an unpredictable collaboration with nature. In this process, I reset my own time to clay time, revelling in the lethargic and cathartic digging, filtering, sculpting, collecting and firing process. The surfaces evoke the land they are made with, in and for, reflecting my prioritisation of organic reappreciation. The pots bring a celebratory focus to a domestic, feminist space as I learnt techniques from talented women on YouTube all over the world, who enhance loved and cared for homes. Slowly, lovingly and naturally created, they truly embody William Morris’ iconic ideology. And my favourite thing, the reconnecting to nature does not here as the pots themselves prompt foraging for flowers to fill them.

Instagram: @cecilylj

website: cecilyloveysjervoise.com

[08] Zakia Carpenter Hall

I started by looking at the transcript of one of William Morris’ speeches, specifically ‘Hopes and Fears for Art’, and as I read through the speech I was delighted to find that Morris used a lot of earth and flower related metaphors in his lecture. So I created a separate document of William Morris’ quotes with flower references or metaphors in them.

I began the project already having wanted to write from the perspective of flowers and I enjoy reading writer’s lectures. I had recently revisited Margaret Atwood’s Negotiating with the Dead based on her lectures at the University of Cambridge, and I was familiar with the idea of the ‘Last Lecture’. So I decided to do a series of poems called ‘The Flower Lectures’. It had everything I wanted from my original idea without sticking to a specific poetic form, and I found the new idea interesting and compelling.

With the first poem lecture, I decided to start with what the flower may be expected to speak about and then subvert that. Exploring the topic of meaningful work and craftsmanship helped me to write from the imagined flower persona. It could also be said that I attempted to find aspects of my own personality that are most ‘flower-like’ and write from that place. The final poem, ‘The Life Cycle of Roses’, a poem of both celebration and mourning felt fitting as a part of this series.

Twitter: @ZCarpenterHall

Website: zakiacarpenterhall.com

[09] Martine Hess & Nora Vatland

Under capitalism, both workers and environmental resources are being pushed beyond their limits and beyond repair. With the help of William Morris’ eco-socialist principles, we take a closer look at the destructive sides of capitalist production: From environmental degeneration to exploitative labour and lack of creative freedom. Morris found capitalism to be “ugly” and advocated for a sustainable and equal future. More than 100 years after his death, the concerns he raised, and the faults of capitalism which he spent much of his lifetime criticising, still apply. A fresh start is needed to create this desired future and we can look to the past and Morris’ words for guidance.

Instagram: @itsnuet, @martine.hess, @noramvatland

website: itsnuet.com

[10] Mónica Arroyo Berezowsky

“Colibri”

Nature knows best when it comes to auto regulation and sustainability. It is a complex system in which every element plays a key role in keeping harmony and balance. Sadly, our society has evolved into an anthropocentric model which assumes we have some kind control over our environment.

Ecosocialism is a vision of a transformed society in harmony with nature, one that is present in William Morris’ prose and meticulous aesthetic. The textile designs of this Nature Boy are the perfect marriage of equilibrium and symmetry, we can appreciate it in his use of flowers and birds, and in the beautiful metaphors that his choice of materials entail.

Colibí is a project that combines the essence of the Mexican culture and the ideals of ecosocialism. Although most of the world has evolved into a globalised society, there are still many aboriginal communities that live in consonance with nature; taking inspiration from their symbolism and considerate use of materials, this project intends to explore embroidery as a way to apply our creative practice in a sustainable way.

Colibrí is an ancestral word which means “hummingbird”. It is a constant symbol present in most Mexican embroideries. In pre-hispanic cultures, the hummingbird was known as a messenger, a keeper of nature’s balance. It is with this motif that I aim to transform the semiotic context of this bird into a symbol of eco-socialism; a visual metaphor that combines flowers, a fingerprint of William Morris, and symmetry.

Instagram: @moni_abere