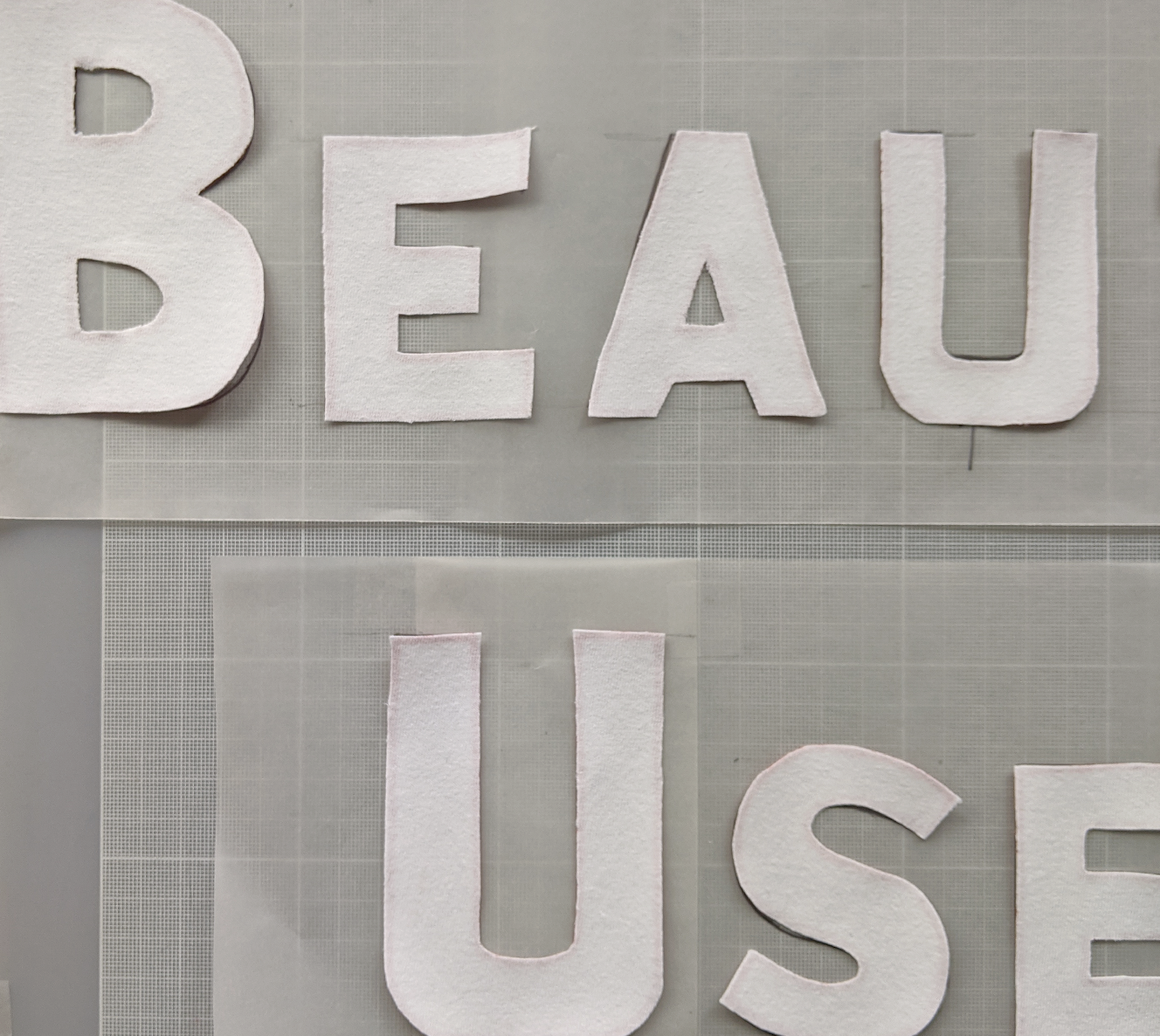

Storybox 03:

Have nothing in your

house that you do not

know to be useful or

balieve to be beautiful

[19] Sadie Cook

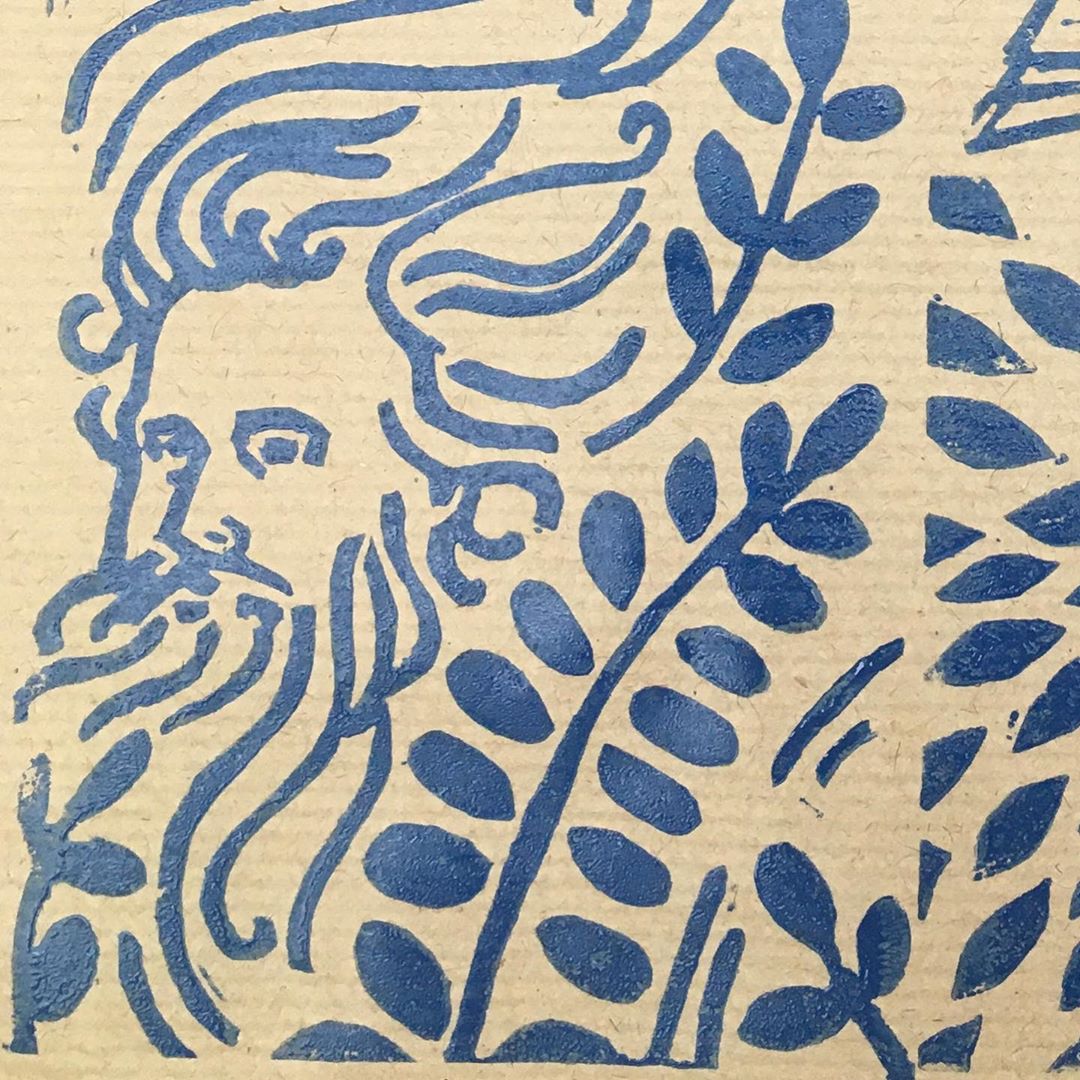

BEAUTIFUL / USEFUL proposes a line of descendency between the Socialist activities of William Morris in Hammersmith and Wimbledon in the late 1800s and the co-operative beginnings of AFC Wimbledon football club in the early 2000s. It is inspired by the home-made flags of England fans, and uses the colour scheme of the Democratic Federation, Socialist Society, Socialist League and Saint George’s Cross. True to the environmental concerns that Morris held dear and which are now an urgent concern, the materials used are all recycled / donated.

‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.’ (lecture: The Beauty of Life, 1880). Over the last century and a half these words have inspired many to reconsider and rationalise their belongings; they are still resonant today, with Marie Kondo having much the same message for her followers. As my research developed, I began to hone down questions around accepted societal norms – when is being part of a crowd useful? Is sport beautiful?

Created during the Covid-19 pandemic when audiences are poignantly absent from stadia, the work has echoes of protest banners, and the paraphrasing of the Morris quote encourages the viewer to questions of beauty and usefulness beyond the home into a broader context of sport, in particular “the beautiful game”.

Instagram: @_sadiecook

website: sadiecook.com

[20] Mar Rubio Coderch & Sol Rubio King

3 FUROSHIKIS FROM SOUTH LONDON

Nettle leaves. Oak Galls. Dock roots

We are Sol Rubio King (4 years old) and Mar Rubio Coderch, a graphic artist and printmaker.

This project pursues the making of three screen printing inks using mainly locally foraged plants. The restrictions imposed by the lockdown inspired this project by producing a mother-daugther collaboration in which daily walks, foraging, writing, drawing and experimentation with colour-making merged together to produce three Furoshikis (multipurpose cloths).

Each of these Furoshikis is printed with, and has a design inspired by, each of these plant elements; nettle leaves, oak galls and dock roots.

We started with one question, can we make a screen printing ink with local plants that can print on fabric and resist washing? And we find out not just that but something that we value even more, a slow and enjoyable process, that connected us more with surroundings and that opened doors to more questions.

The slowness of the whole process, involved reading about plants, foraging them, drawing and writing their names to create patterns, making screens with the designs, making ink from them, preparing the fabric to be printed, printing it, steaming it, neutralizing it, and sewing the edges. This slowness also made us think about the value of the origin of the consumed products, about their toxicity, about the enjoyment of the process of making something from scratch, selecting and manipulating each of the ingredients used and about the concept of durability.

To find more about the project follow @camino_studio

website: cargocollective.com/caminostudio

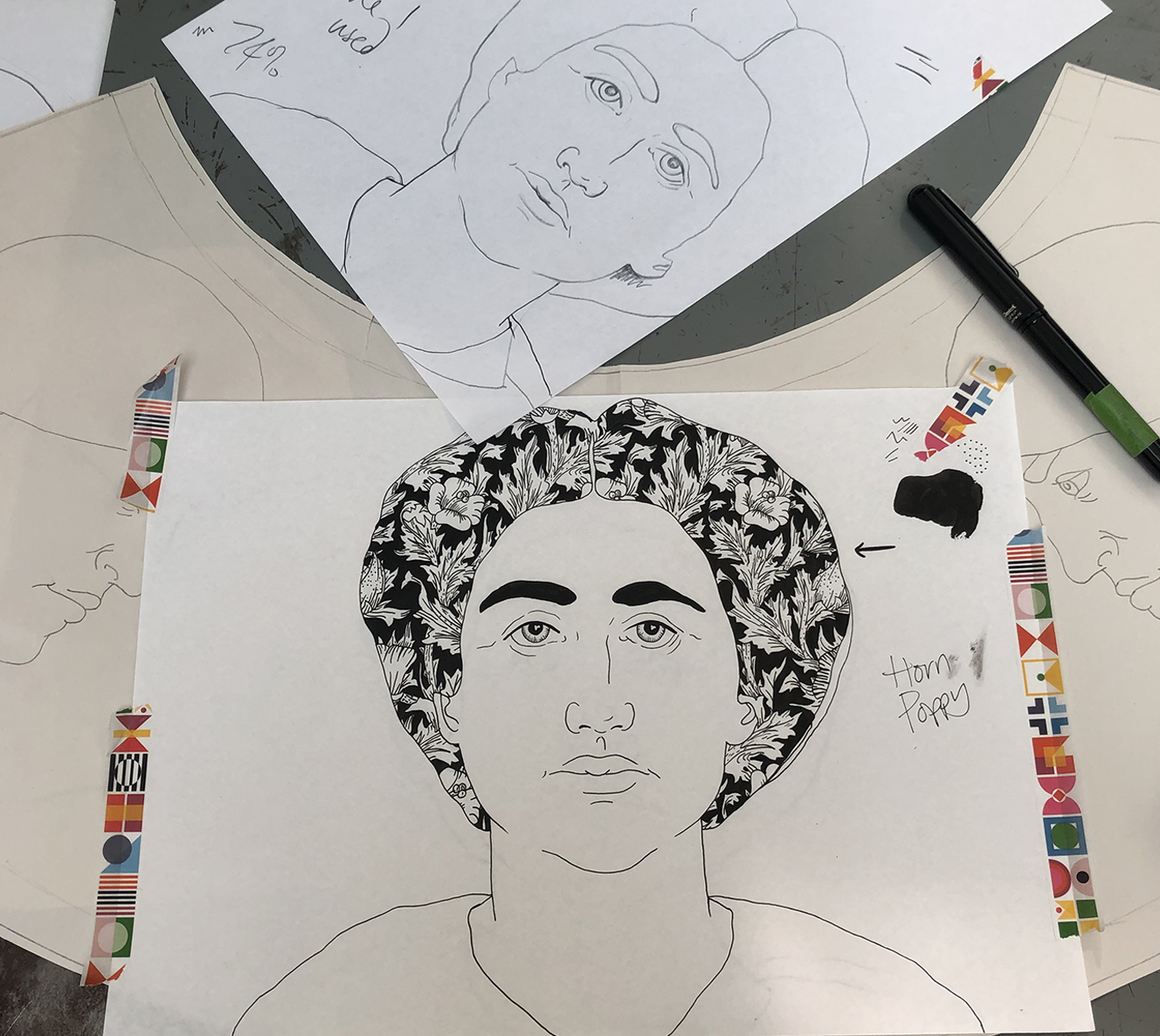

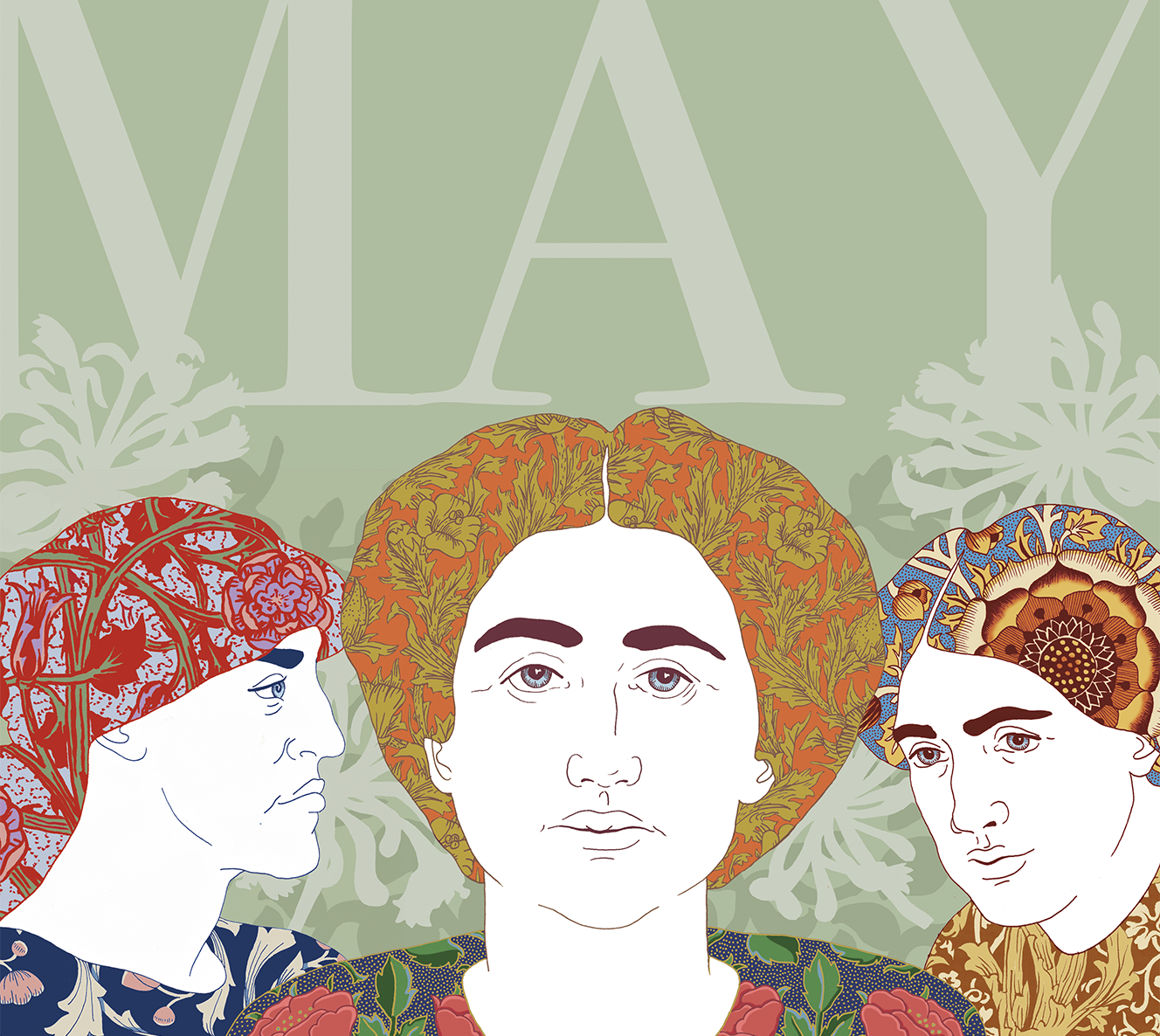

[21] Anna German

My research is centred around May Morris. Though a pivotal part of the Morris legacy, both in a professional and private sense, her father’s phenomenal success has overshadowed May’s own significant achievements and her influence on the design landscape within the UK has not brought her the renown she deserves. When considering how to respond to May’s life in a practical sense, I thought carefully about what Kathryn Hughes wrote: ‘May’s whole practice lay in the articulation of simple forms, whether drawn from nature or vernacular art, made up into practical well-made items for everyday use. What she particularly loathed were overdecorated goods designed mainly for display.’ With this in mind, I have brought together May’s image with fragments of her inspirational design work in a design for a lamp shade.

Instagram @frau_deutsch_

[22] Marta Cabeddu

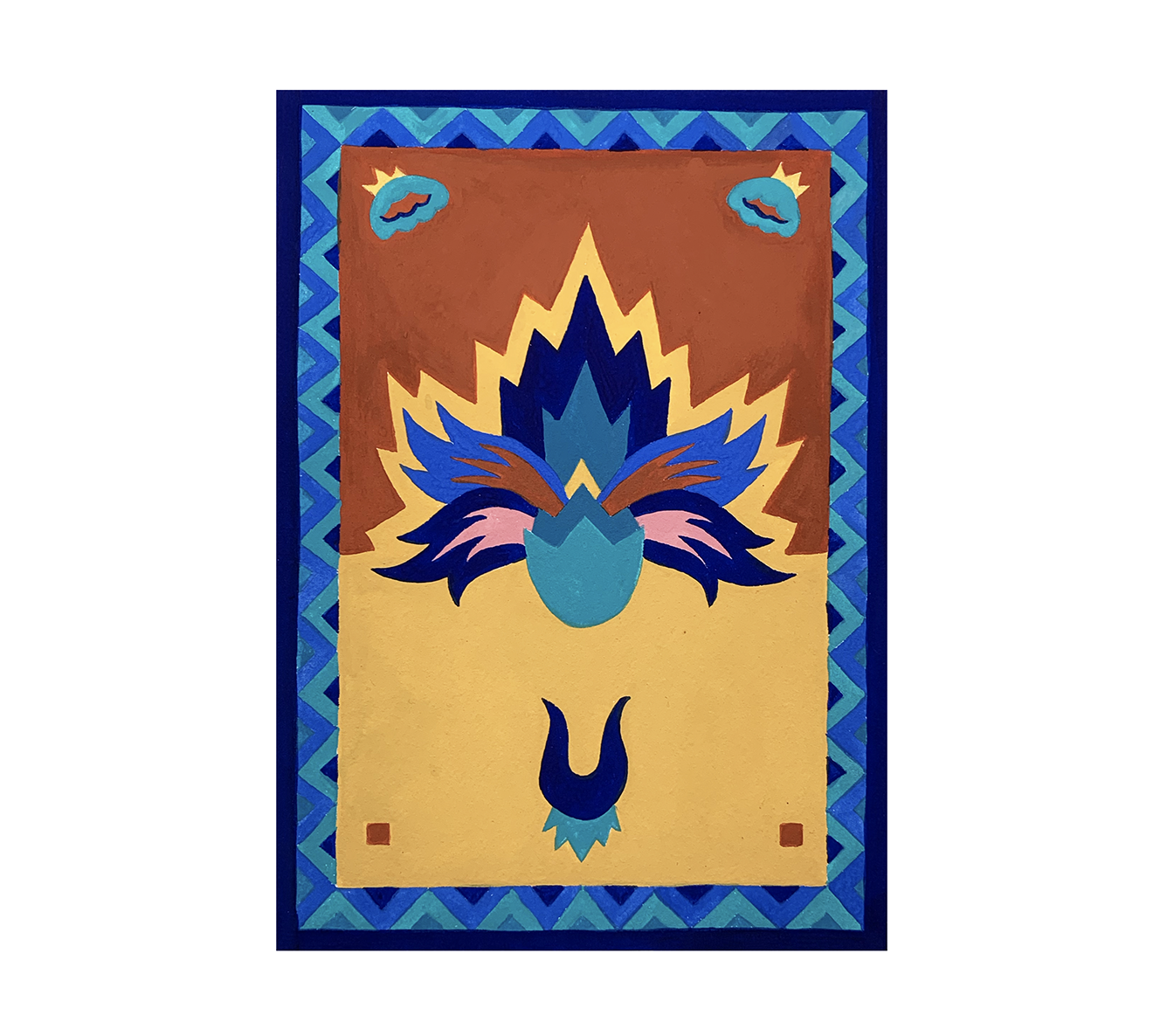

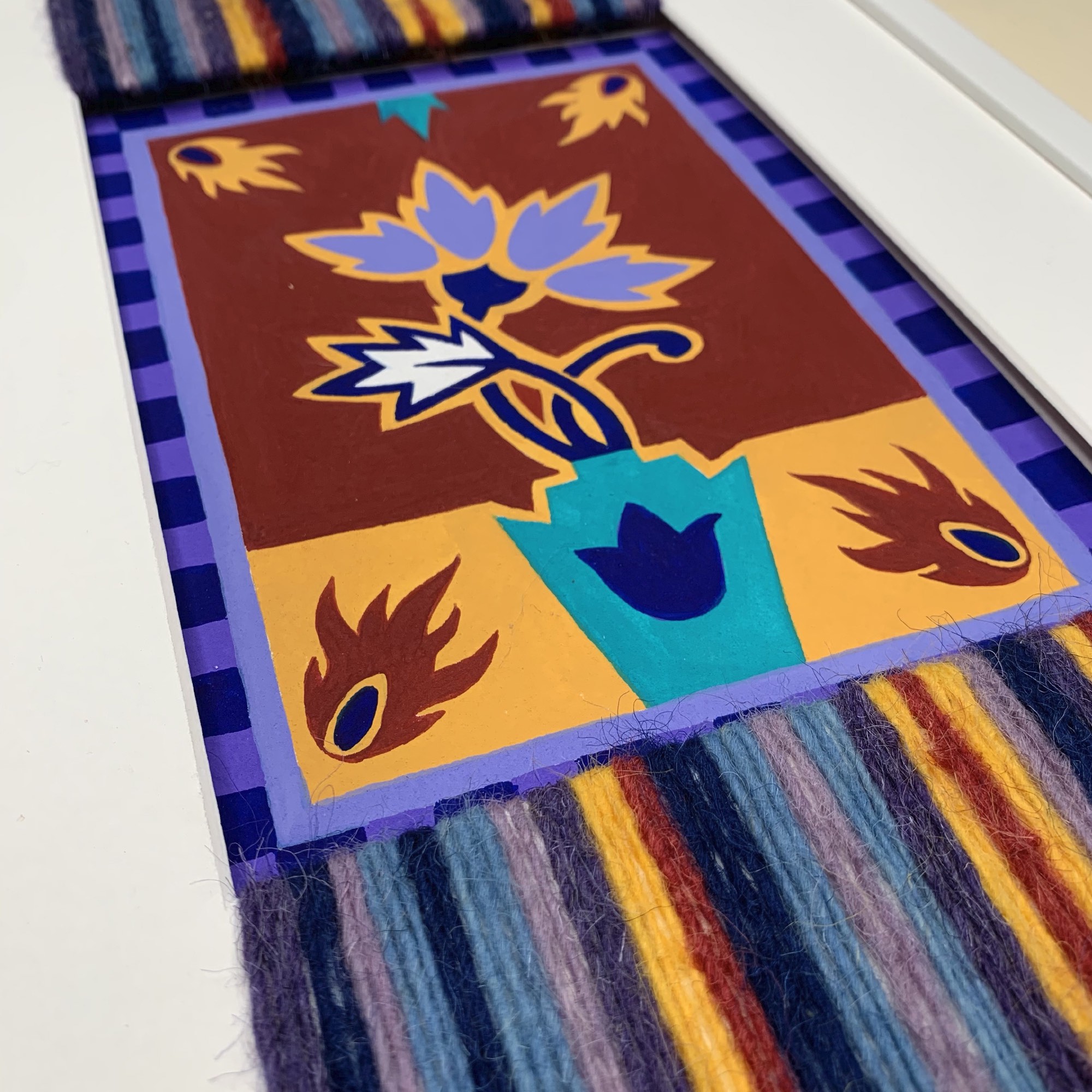

When I started my research about William Morris and his work, I immediately recognised something familiar. I’m Italian and I was born in Sardinia, but I noticed how the art and craft of my culture share many of the ideas and philosophy of William Morris. This for me was a starting point for a reflection about the real value of things.

The importance of the hand-made, the techniques, the skills of the crafter, the time dedicated to the creation, the heritage and the tradition, the attention for organic material are all factors that make objects timeless. Something opposite of fast-fashion: a slow, sustainable and local production circle.

This project gives me the chance to reflect on the fact that a different and more sustainable way exist. That it’s better to have less but have better. I chose the symbol of rugs and painted a series which are a mix of elements inspired by William Morris’ work, elements taken from Sardinian textiles and elements that come from my personal practice.

I asked to my family and friends to send me pictures of the object they could find home, that in every family here in Sardinia are kept as treasures. With all of them, I had great moments of sharing and interesting conversation that made me understand more than ever of what those objects represents. My “rugs” are framed creating fringes using Sardinian organic wool and there is a zine which includes the notes, sketches and the final design.

Instagram: @martacubeddu

website: martacubeddu.com

[23] Leo Russo, Amy Turnbull & Joseph Montagu

Artistic Dress 2020 [The William Morris Tracksuit]

William Morris didn’t often comment on dress. Dress in Victorian times was (by contemporary standards) restrictive, uncomfortable, stuffy, formal, and deeply gendered. According to a lecture given at the forest school by Mhairi Muncaster (Development manager at WM gallery), Morris believed in what he called ‘artistic dress’ which was comfortable and more loose-fitting. He also provoked controversy by saying that women should reject their crinoline and corsets because of their un-comfortability. “Do not allow yourself to be upholstered like armchairs” he is quoted as saying in one 1880’s lecture.

In his visions which stretched far into the past and inconceivably to the future (now present day in the 21st century), we think Morris imagined that we could all wear clothes like monks do: fabrics designed for simplicity and upmost comfort (a necessary aspect of life when extended periods of prayer and contemplation are prerequisite!). The belief that form and function must find equilibrium in clothing carries through to Morris’s commitment to fabric design. Morris held nature as the ultimate inspiration, and concurrently the depictions of nature found in medieval illuminated manuscripts. From the Harley Manuscript in the British museum, which depicts the Garden of Pleasure from Le Roman De La Rose, he wrote in one essay that ‘a garden should clothe the house’ (Braesel 2004), drawing direct connections between pleasure, function, comfort, and Morris’ idea of cloth.

Some of Morris’ fabrics would be sold as dress lining in the late 19th and early 20th c. but it wasn’t until the 1960’s that ‘Granny Takes a trip’ would reimagine his curtain and upholstery fabric as fully fledged jackets, popularised iconically by George Harrison. Morris’ ideas from socialism are well documented, with crucial ideas such as the preservation of ancient buildings for future generations and the ‘just price’ for manufactured products being no doubt influential precursors to the contemporary ideals of social and sustainable design.

For this story box, we have decided to reimagine the concept of artistic dress for the young creatives of the 2020’s. Nothing seems more fitting and more comfortable than the tracksuit. The most accessible, universal and utilitarian dress of our day, worn by creatives and non-creatives alike. The tracksuit is a part of British cultural identity, revered as much by art students as it is athletes. With the luxury of digital technology and mechanised processes, the handmade can become affordable, bridging a gap that Morris wasn’t able to. Machine rendered recreations of the original patterns will be carved into photographic emulsion with upmost precision, and within a couple of hours, a screen print can be prepared that would have taken Morris’ workers weeks. This enables the hand printed fabric components to be hand assembled by skilled craftspeople in so much as an afternoon.

Artistic Dress 2020 [The William Morris Tracksuit]

Photography by @naomimadigan

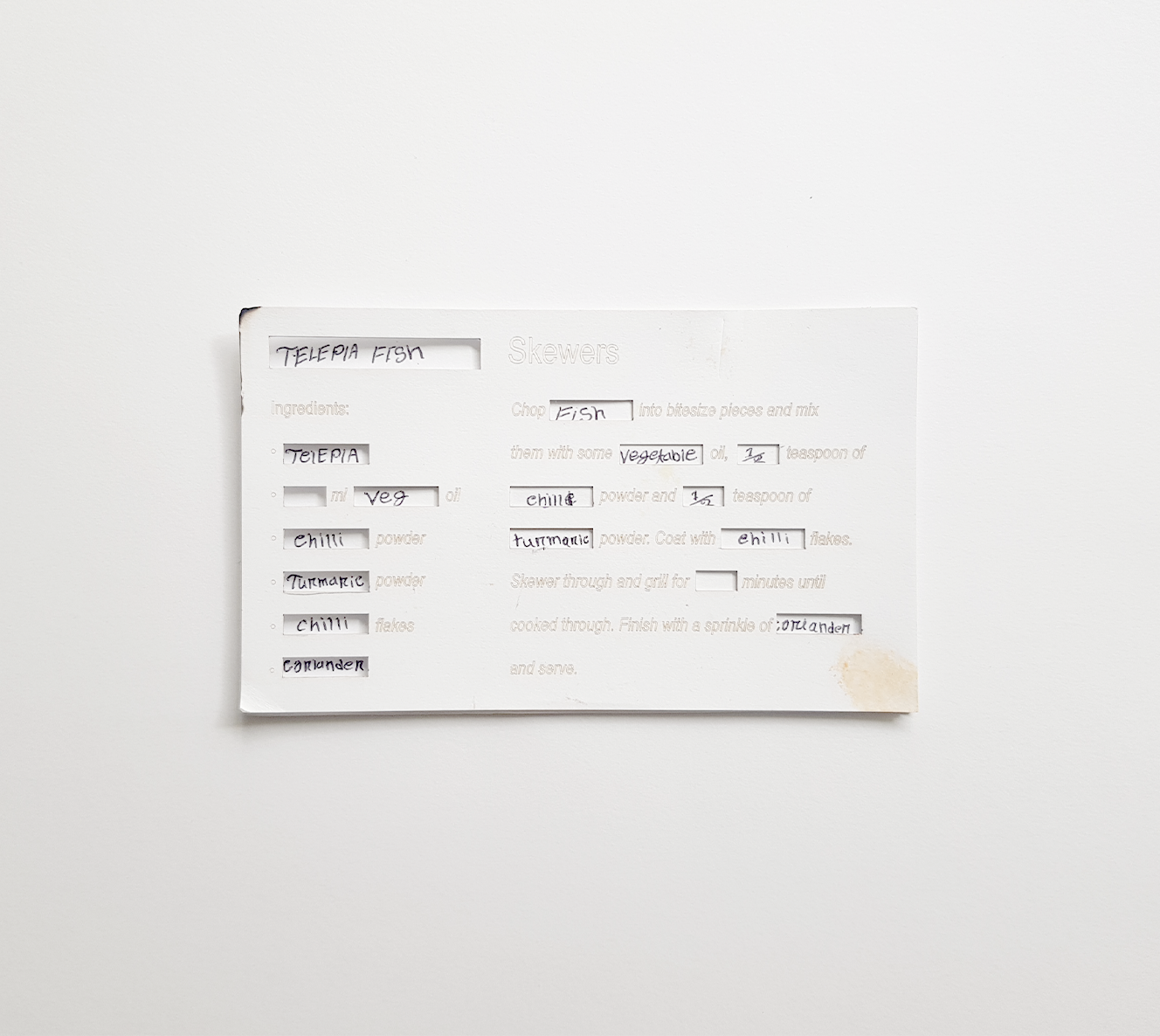

[24] Tabassum Aktar

Morris identified that with the popularisation of mass production came simple, unskilled work. He believed this was not ‘honourable work’, which requires creativity, imagination and intellect. For example, factory workers making chairs will each have one task that would collectively make a chair. The crafter, as opposed to the worker, is with the journey of the chair from raw materials to a functional member of the house. The maker has more fulfilment and the chair has more value because it was lovingly made and is the product of their own imagination and skill.

I made three discoveries during my research: the possibility of human error in a product is important to the value of it; creativity is an essential part of mental health; skilled work produces more intellectually and emotionally flourishing people. Removing elements from instructions coerces people to use their own imagination to replace the missing words. I did this to a recipe because when it comes to cooking, the modern-day approach is to google a recipe that was ‘perfected’ to someone else’s taste, thereby removing any human error or creativity. By using suggestive language, the collaborators created dishes that were mostly different with shared similar traits, using the exact same recipe card.

The result is a product of someone’s mind, soul, body, memory and imagination; plus, a sense of ownership, happiness and fulfilment. As a designer and maker in the industry, I know that Morris’s words are as true today as they were over a hundred years ago.

Instagram: @Tabassum_Aktar

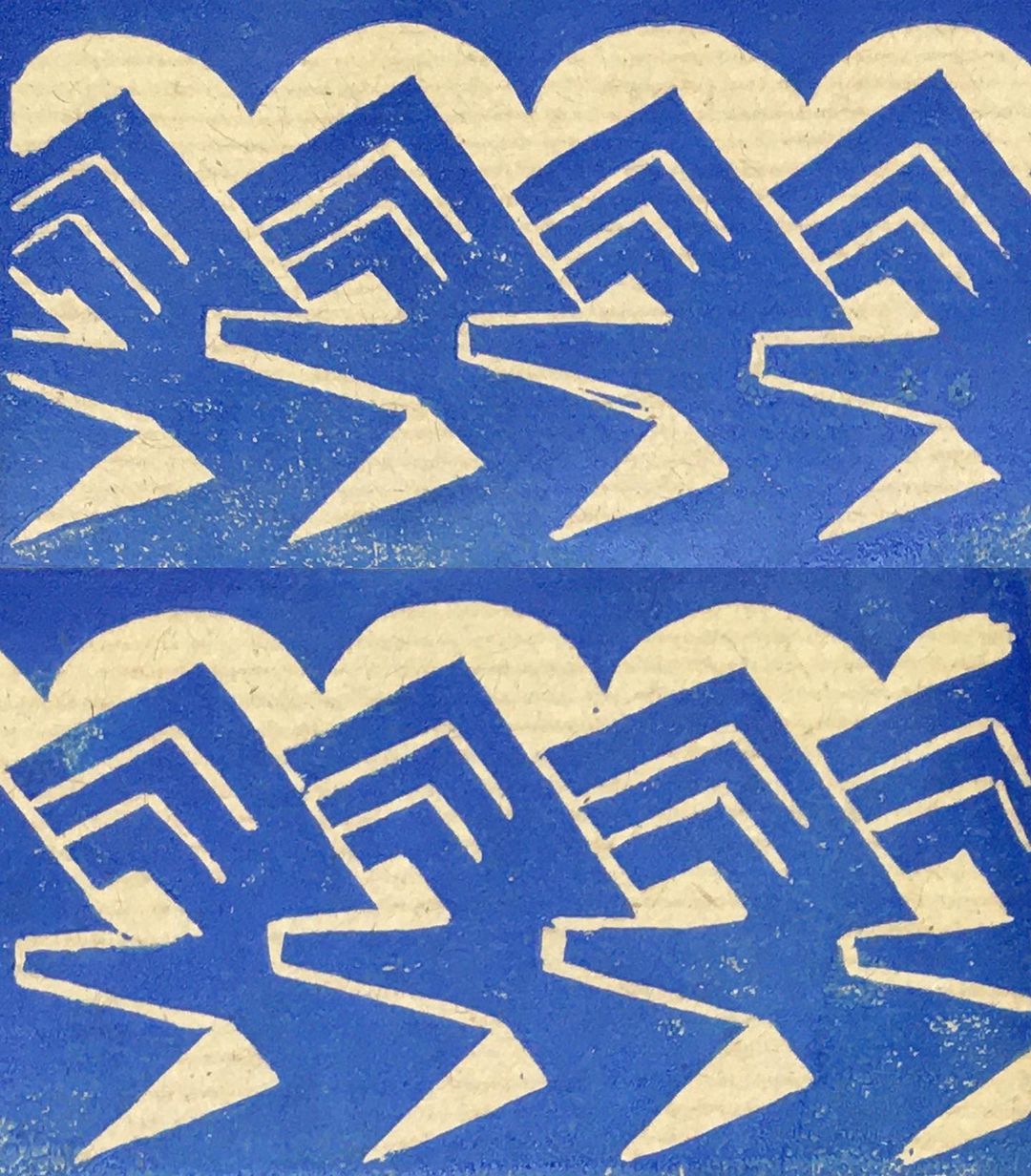

[25] Julia Buckley

Morris and the Blue Vat

“I am taking in dyeing at every pore…”

Morris developed an obsession with the indigo dye vat and his letters testify to his hands-on approach to this process. The dye features in many of his designs and appears in archive items held by the Morris Society such as his wallpaper pattern book and textile print for Borage. His rejection of the aniline dyes of the Industrial Revolution not only demonstrate an aesthetic preference for natural dyes but reflect his passion for the motifs and resources of the natural world and his interest in the revival of traditional crafts. It could be said that this predisposition towards natural hues was ingrained in Morris from birth; he writes of the indigo and madder decorating the “…rag from the bed which heard my first squeak”.

Inspired by Morris’s work, I experimented with my own indigo dye vat; experiencing both the delight and frustration resulting from this somewhat serendipitous process. I looked at Morris’s route into the use of indigo through traditional texts such as Gerard’s Herball of 1597; a publication from which he drew visual and contextual influence.

My visual response is multi-layered and intends to reflect the wonder of the physical process of indigo dye itself to the wider implications for the collective efforts of craftsmanship and the tactile relationship between craftsman and product. My outcome aims to express our inherent affinity with those colours derived from nature and the sheer exuberant joy Morris attained from this colour.

Instagram: @jbuckley2424

[26] Izzi Lombardo

Like many of us this year, being stranded within the four walls of my apartment over the last few months, I had time to observe my home environment like I have not been able to before. With time on my hands I set out to modifying all manner of objects around me. Nothing was safe. Not being able to create anything from scratch put interesting limitations on my creations. Paying attention to the details of my life in this way, it became blindingly obvious that so many of the objects do not serve their function in my world. Neither could any mass manufactured thing, unless they could all sit in the exact same kitchen in the exact same place in every person’s exact same routines and lives. And where is the fun in that? Our lives and habits are all different, so should be our objects. When we spend time adjusting our environment to fit our need we cultivate a relationship with it. We grow it, we love it, we do not over consume it. We do not throw away a broom simply because the handle fell off, we mend it. We do not throw out our chair because it is not soft enough, we add a cushion. We adjust. Through forming relationships with our objects, we learn how to fix them and how we can adjust them better to fit our needs. Whether it be function lead or to make us chuckle. Refusing to participate in this culture of consumerism is a powerful act of rebellion.

Instagram: @izzi_lombardo